Leonardo Badea (BNR): The economic dynamics of the last quarter of a century in Romania and the current need to re-balance public finances

From this perspective, it can be useful to look at the evolution of some relevant indicators, over a longer time horizon and in comparison with other economies in the region.

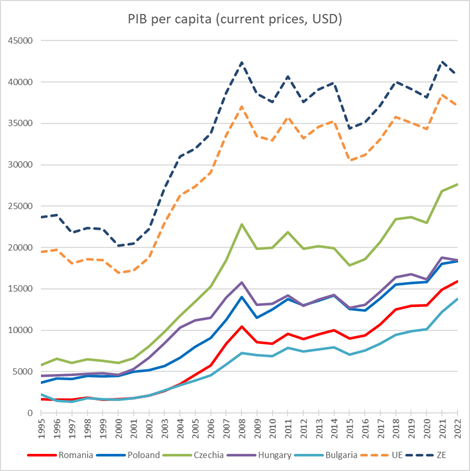

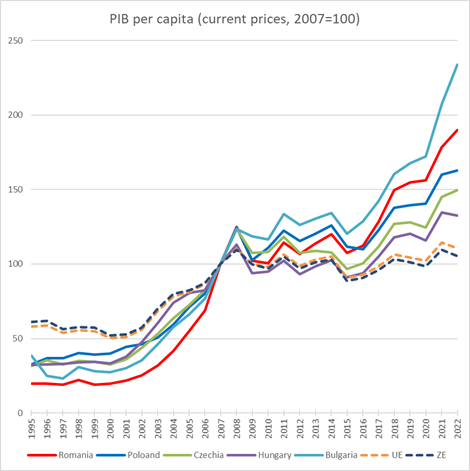

Figures 2 and 3 above, based on data published by the World Bank, confirm that Romania’s economic progress over the past 27 years has been remarkable. But the same can be said about Bulgaria, Hungary, the Czech Republic, and Poland, as well as about the European Union as a whole. However, the graphs indicate particularities of different time periods and different dynamics between countries.

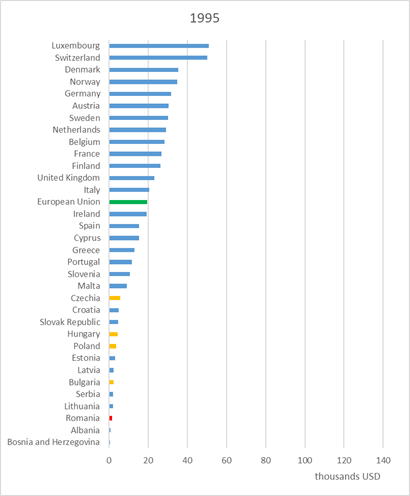

In 1995, Romania had the lowest level of GDP per capita in the region ($1,650). We could say that then, in 1995, Romania started the race of these last 27 years from the last place in relation to its neighbors. At that time, GDP per capita in Bulgaria was 37 percent higher ($2,259), in Poland it was more than double ($3,687), in Hungary it was more than 2.7 times higher ($4,495), and in the Czech Republic more than three and a half times higher ($5,824).

This landmark in time is not chosen by chance: in June 1995, Romania submitted its application for accession to the European Union. There followed discussions, negotiations, great efforts for all those involved, and the progress towards this state objective, the EU membership, was, especially in the first years, painfully slow (something that can be explained by the very large gaps we had in almost all fields).

Between 1995 and 2001, however, several important stages were completed: in July 1997, the European Commission adopted Agenda 2000, which included the Opinion on Romania’s application to join the European Union; in November 1998, the European Commission published the first Country Report on the accession process of Romania; in June 1999, Romania adopted the National Plan for Accession to the European Union, and in December of the same year, in Helsinki, the European Council decided to start the accession negotiations with six candidate countries, including Romania; in February 2000, during the meeting of the General Affairs Council dedicated to the launch of the Intergovernmental Conference, accession negotiations with Romania were officially opened, a historic step that radically changed the country’s development prospects.

Returning to the economic perspective, until 2000-2001, the evolution of GDP per capita (calculated in current prices and expressed in hard currency) was oscillating, the overall picture being one of stagnation. The economy and society were fully experiencing the costs of the years of discretionary, centralized, and inefficient management and organization of the economy during the communist period, and the necessary adjustment to market mechanisms was not going to be easy. It is relevant in this context that during the period 1995-2001, the annual inflation rates were double-digit and sometimes even triple-digit. For example, for 12 consecutive months from February 1997 to February 1998, the annual inflation rates ranged from 105.4 percent to 177.4 percent. Also as an example, in December 1996 and in each of the first three months of 1997, the monthly rate of inflation (the average increase in the prices of goods and services in the consumer basket from one month to the next) was consistently above 10 percent, and in March 1997, i.e. in a single month, it was 30.7 percent. Also in the period 1995-2001, the nominal exchange rate of the leu against the US dollar depreciated almost 18 times. In December 1994, one US dollar was exchanged for 1,767 ROL (old lei, before the denomination, the nominal equivalent of 0.1767 RON today), and in December 2021, it had already reached 31,567 ROL (the nominal equivalent of 3.1567 RON today). The figures are shocking for those who no longer remember that period. They were difficult years and there was a great pressure on the population.

Looking back from then until now, in that early period it was quite difficult to implement reforms for the future. But they were implemented, and time has proven that it was a good choice.

Regardless of the circumstances, the reforms must be carried out, all the more so since, although the current situation is complicated, Romania benefits from the substantial financial support of European programs. I am convinced that today as well as then, the reforms must be implemented, and the positive effects they will have over time will confirm that they are a good choice this time around as well. It may seem exaggerated, but from a certain perspective, the importance of the present moment and the way the decisions we make now can bring us closer to the goal of adopting the euro, I think can be compared to those of the period 1995-2004 and the reforms that allowed the unequivocal entry on the path of accession to the European Union.

Returning and continuing the analysis, the graphs of many economic indicators show that the year 2002 marked an important positive turning point in Romania’s evolution, which finds a counterpart in the plan of actions and political decisions. The month of November 2002 recorded the adoption by the European Commission of the “roadmap” for Romania and Bulgaria, as well as the first official mention in the European Parliament of January 1, 2007 as the target date for Romania’s accession to the EU. In December 2002, the European Council in Copenhagen decided on the accession of ten new member states and adopted the roadmaps for Romania and Bulgaria. Economically, in 2002, Romania managed to increase its GDP per capita by over 16%. Six more years of accelerated growth above 20 percent each year would follow. For example, in 2007, the year Romania effectively became a member state of the European Union, GDP per capita increased by over 45 percent. The series would be interrupted by the effects of the global financial crisis and, subsequently, of the European debt crisis.

The graph in Figure 3 above changes the time frame and sets the year 2007 as a reference point, from many political and economic perspectives a milestone of particular importance in the subsequent evolution of the country. A period of relative stagnation is observed until 2017 (compared to the maximum of 10,435 dollars per capita reached in 2008), certainly under the influence of the financial and economic crises that affected most European states (visible on the graph), and later a return of the sustained growth trend over the past six years. The annual rhythms were different, during this period the impact of recent crises was felt and it affected the progress but did not reverse the trend. The graph highlights the year 2020 (strongly influenced by the onset of the Covid-19 pandemic), when GDP per capita practically stagnated in the case of Romania, but also the following year, when it grew at a rate of around 14 percent, comparable to those of 2017 and 2018.

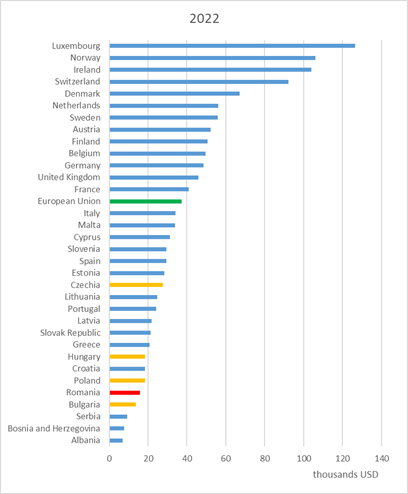

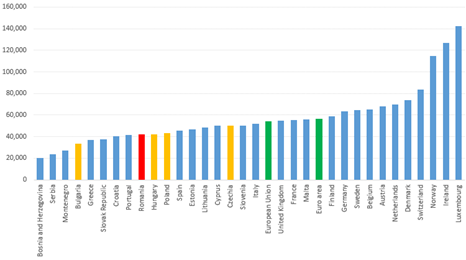

The trends in the evolution of GDP per capita described above for Romania are correlated with those of the countries in the region, but also at the overall level of the European Union. Figure 4 compares the level of GDP per capita only between the beginning and end years of the analyzed period, respectively 1995 and 2022, but for a much wider selection of European states. Because it started with a very large gap, although it grew very quickly, in the last 27 years Romania has gained only two positions in the regional ranking, surpassing Bulgaria and Serbia, but still remaining behind Poland, Hungary, and the Czech Republic. However, the differences (in percentage terms) are much smaller in 2022 compared to the 1995 levels. Compared to the Czech Republic (the most advanced in the region), we now have a gap of 74 percent, which is an improvement from the 253 percent in 1995. Poland and Hungary outpace us by 15 and 16 percent, respectively, from 123 percent and 172 percent, respectively, in 1995.

Like other indicators of the dynamics of the economy, GDP per capita can be calculated in several ways:

- by conversion to a widely circulated currency (for example dollars as above or euros – for data analysis after 1 January 1999 when it was introduced, first for accounting and electronic payments, and from 1 January 2002 also for cash transactions, with euro coins and banknotes being launched);

- by reference to the average of a certain wider economic area (for example, the European Union in the case of member states);

- or at purchasing power parity. According to the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), purchasing power parities (PPPs) are currency conversion rates that attempt to equalize the purchasing power of different currencies by eliminating differences in price levels between countries. The basket of priced goods and services considered in establishing PPP is a sample of all that is part of final expenditure: final household and government consumption, fixed capital formation, and net exports. This indicator is measured in terms of national currency per US dollar.

Analyzing the three approaches to calculating GDP per capita, we could say that the first is probably the most conservative, because it uses hard currency conversions of economic results, without considering very important particularities, such as the relative level of incomes and of prices, among the countries compared. Discrepancies can be large when the degree of development differs greatly among the countries in the sample, so especially when comparing economically advanced countries with countries in the category of emerging economies. In such situations, some economists believe that using PPP is more appropriate because the method incorporates adjustments for these differences.

In our case, economic intuition would probably suggest that when we compare Romania with Bulgaria, Hungary, Poland, and the Czech Republic at a time close to the present, the differences may not be so great that the applied method changes the ranking. For the sake of rigor, we have verified this by making a ranking of GDP per capita levels in 2022 similar to the one in Figure 4 above, but this time based on purchasing power parity. It can be seen from Figure 5 below that Romania’s position in the group of five countries on which the present analysis is focused has not changed, ranking higher than Bulgaria and only slightly lower than Poland and Hungary. Also, the position of undisputed leader of the group of five countries in the GDP per capita ranking for 2022 is still held by the Czech Republic. So, things remain almost unchanged compared to the graph on the right in Figure 4 above, expressed by GDP per capita in US dollars.

Interesting and at the same time relevant from this comparison between methods is the observation that, when we adjust with the different level of prices (when we make the transition from GDP per capita expressed in US dollars to GDP per capita taking into account PPP), Romania ranks in 2022 over Slovakia, Croatia, Greece, and Portugal, as shown in Figure 5 below (as opposed to the right-hand graph in Figure 4 above). The change in Romania’s position in the ranking compared to Greece and Portugal due to the change in method shows precisely the fact that PPP reporting brings a new (and at the same time relevant) angle to the analysis, especially when the compared countries have significantly different levels of overall economic development.

Economic growth is only part of the big picture. Many other things matter: how sustainable is the growth in terms of the components that contribute to growth, what are the determinants (both endogenous and exogenous in nature), what is the magnitude of the negative externalities it generates (e.g. on the environment, communities, etc.), what effect does it have on social inclusion and development, etc.

Since for Romania’s economy the twin deficits currently represent an important vulnerability with impact on future development prospects, it is useful to continue the comparison at the regional level by studying the dynamics of the budget balance, which implicitly has an effect on the current account balance.

If we analyze from a historical point of view the periods with large budget deficits that led to the increase of public debt, we notice that they were often associated with severe economic crises or wars. Indeed, there are also periods when the deficit was the effect of a long-term structural mismatch between revenues and expenditures in the general consolidated budget. This “mismatch” was in turn amplified by the temptation of populist policies that reinforced the usual trap of pro-cyclical measures with long-term destabilizing impact.

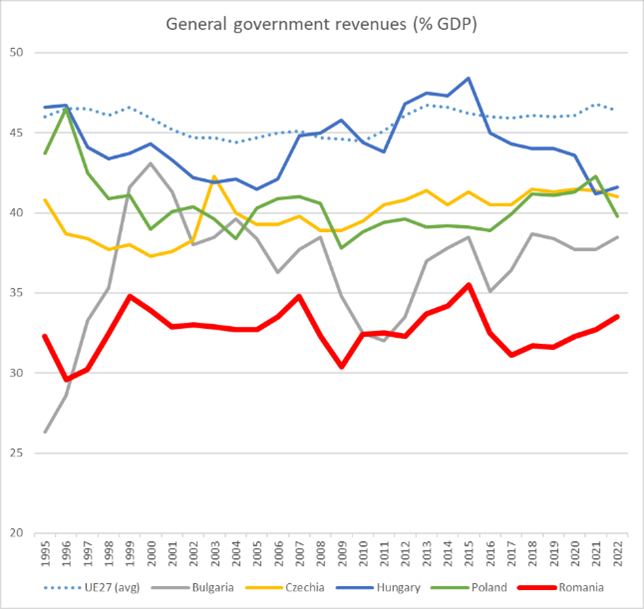

The observations formulated above are not specific to Romania. However, as shown in Figure 6 below, one of the elements that made Romania unique within the region during the last 27 years was the constantly lower level of budget revenues (as a share of GDP) compared to other countries. Not for one year, not for five, not for ten, but for twenty-seven years in a row, the share of the revenues of the general consolidated budget in the GDP was significantly lower in Romania than in Poland, Hungary, and the Czech Republic. Including in Bulgaria, the share was in most of this period higher compared to Romania, with the exception of the years 1995-1996 and 2011.

This shows that, in relative terms, the autonomous financial resources available to support economic development programs and to fight against the negative effects of crises of all kinds were for 27 years lower for Romania than for Poland, Hungary, the Czech Republic, or Bulgaria (in the case of Bulgaria with the exceptions mentioned above).

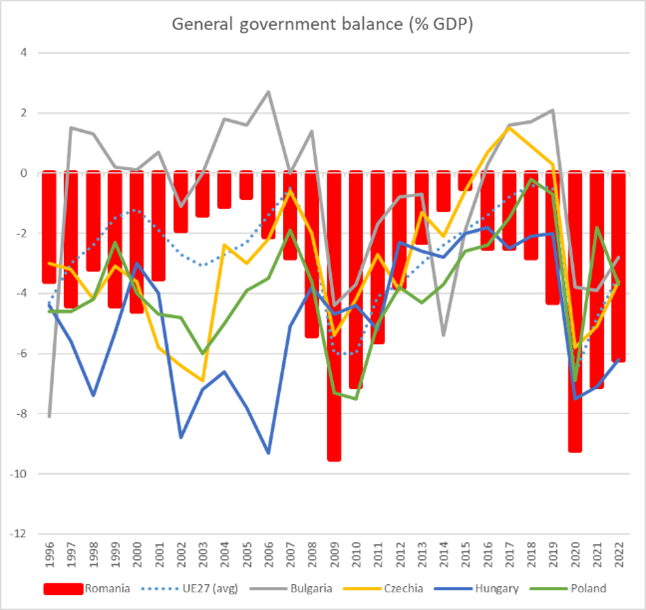

Starting from this reality, we understand that the larger budget deficits we have had in some periods of time within the mentioned group of five countries (see Figure 7 above) were not only the effect of structural weaknesses or out of control dynamics of budget expenditures, but also of the lower level of income.

Figure 7 also shows that, in the last 27 years, Romania had two clear periods of extensive consolidation of the general budget: the period 2001-2005, followed by the years 2006-2007 in which the deficit remained below 3 percent and, respectively, the period 2010-2015, followed by the years 2016-2018, also characterized by deficits within the limit of 3%. It is true that the reforms were carried out (in some cases) with the support of international bodies and under the pressure of certain conditions assumed as a result of our integration process in the European Union. In 2019, as in 2008, the equilibria deteriorated (many of the causes stemming from the imprudent policies of the previous period) shortly before a succession of major crises, making them very difficult to manage and reducing the potential for subsequent recovery.

In Figure 7, it can also be seen that in both 2008 and 2019, Poland, the Czech Republic, and the average of the EU economies had a much more favorable general budget balance compared to Romania, which allowed them to maintain a better control of the deficits in the periods of successive crises that followed and then to return more quickly to the path of fiscal consolidation. The latest example is that, starting with smaller deficits or even surpluses in 2019, the mentioned economies managed to limit the deficits in 2020 (the year of the onset of the Covid-19 pandemic) and subsequently in 2021 and 2022 to much lower levels than Romania.

The pandemic crisis and the effort to support Ukraine have affected the rather fragile balance of the national budget. This did not happen only in Romania, but here these expenses led to a wider deterioration due to the imbalances from the period before this succession of crises. Precisely in order to have an adequate approach to this complex situation at present, fiscal consolidation must be done gradually, setting realistic milestones. The reform of the public administration and the increase of its efficiency are current priorities, along with the return to an equitable fiscal treatment towards all economic agents, which would allow them to act to overcome the real difficulties of the present, to develop and adapt to the new conditions in a fair competition framework in the market, thus generating economic growth and also increasing budget revenues as a share of GDP.

In a period characterized by a growing level of debt and the need for investment to modernize the economy, the macroeconomic balance of a country matters both in itself, as one of the conditions for sustainable development, and in relative terms by referring to what happens in the countries with which it is usually compared and with which it competes to attract foreign capital and technology. Figure 7 above shows that, as Romania made some corrections in 2021 and 2022, some countries in the region (which started from more favorable levels anyway) made adjustments in turn (for example, the Czech Republic, but also as average at the level of the European Union). Thus, as it happens in dynamic strategies of incomplete information in game theory, the dynamic equilibrium is constantly changing and for now we remain, from this perspective, in an unfavorable position. This is yet another reason why the fiscal consolidation effort must continue and demonstrate clear and lasting (irreversible) progress towards a sustainable level appropriate to our strategic objectives in economic terms, among which an important one is the adoption of the euro within the foreseeable future.