Leonardo Badea (BNR): The Draghi Report | Key takeaways and development opportunities for Romania

The past few years have been challenging in many ways, which remains evident at all levels of society. From an economic perspective, we have undergone significant transformations, navigated multiple risks, and realized certain benefits, albeit not to the degree we might have desired or would have been achievable under more favourable circumstances.

However, the dynamics of economic and social transformations remain much accelerated, and our response through short-term actions and long-term strategic approaches exerts a considerable impact on future development.

Precisely for this reason, it is important not to lose sight of the fact that any period of transformations and structural challenges also entails opportunities for development and improvement. Although acknowledged, this reality is sometimes insufficiently reflected in structural policy approaches. It is essential to recognize and build upon the significant advancements achieved in previous periods. Despite the fact that many aspects have yet to reach the desired level, Romania’s economy has made considerable progress over the past two decades. This progress is evidenced not only by various economic indicators but is also apparent in numerous situations and corroborated by discussions with foreign investors and experts involved in our international collaborations.

Because Romania is an inextricably integrated part of the European Union, many of the trends we observe locally are direct or indirect effects of broader trends in the European and world economy that we experience simultaneously with our European partners. At the same time, the common concerns and efforts of the Union are often opportunities for Romania to exploit its advantages and potential in order to develop and maintain a high pace of convergence, with benefits for the economy and society.

From this perspective, the challenges the EU economy is facing, highlighted once more in the report presented by Mario Draghi, deserve to be taken into account in the periodic effort to reassess Romania’s structural policies and strategic plans regarding economic development. It is worth recalling that the renowned Italian economist was, in turn, Executive Director of the World Bank, Vice-President for Europe of Goldman Sachs, Governor of the Bank of Italy, President of the European Central Bank, and Prime Minister of Italy, accumulating an experience and professional influence which gives special weight to the conclusions he formulates in the recently published report. Although some of the proposals did not achieve unanimous support, I believe it is highly probable that a significant portion of the report’s recommendations will be considered in shaping the continuity of economic strategies by the newly elected representatives of European forums.

Moreover, this is not the first instance of analysing the developmental and competitiveness gaps that the EU encounters in comparison to other economic blocs. Just in April, another former Italian prime minister, Enrico Letta, released a report on the future of the single market and the need to adapt to global challenges. One of its key recommendations was to introduce a ”fifth freedom” in the EU, regarding the free movement of knowledge and innovation, as well as support for education. The aim associated with this proposal was to strengthen technological and research infrastructure, as well as to remove barriers to cross-border knowledge exchange. Since then, much importance has been given to the mobilization of economies, the promotion of investments, the digital transition and the further integration of regulatory frameworks related to these areas.

A notable aspect of the Letta Report was the proposal to enhance transatlantic cooperation and even to achieve a ”single transatlantic market”.

Returning to the Draghi Report, it is centred on the idea of recovering the competitiveness gap in relation to two key economic areas relevant to Europe on the international markets of goods and services, namely the United States of America and the People’s Republic of China. However, relevant for Romania are, in particular, the ways and actions that are proposed to achieve this objective, among which there are worth mentioning: improving productivity (including through digitalization and reaping the benefits offered by AI), increasing investments (especially in technologies and capital goods), revision of energy market mechanisms, reduction of fragmentation of the single market, more efficient use of resources and reduction of external dependencies, more flexibility and harmonization of the regulatory framework, as well as simplification of the European decision-making and coordination framework.

As previously discussed, none of the issues outlined in the Draghi Report are new concerns at the European level. However, one of its key merits is that it presents these issues from a fresh perspective, emphasizing their interconnections and the urgent necessity for action, preferably sooner rather than later. Therefore, I regard the report as a vital new reference point for the debate, underscoring the need for reforms, even amidst potential criticism from various Member States regarding certain conclusions and proposals.

Next, we will address some of the themes of the report from the perspective of our current economic situation and the development prospects.

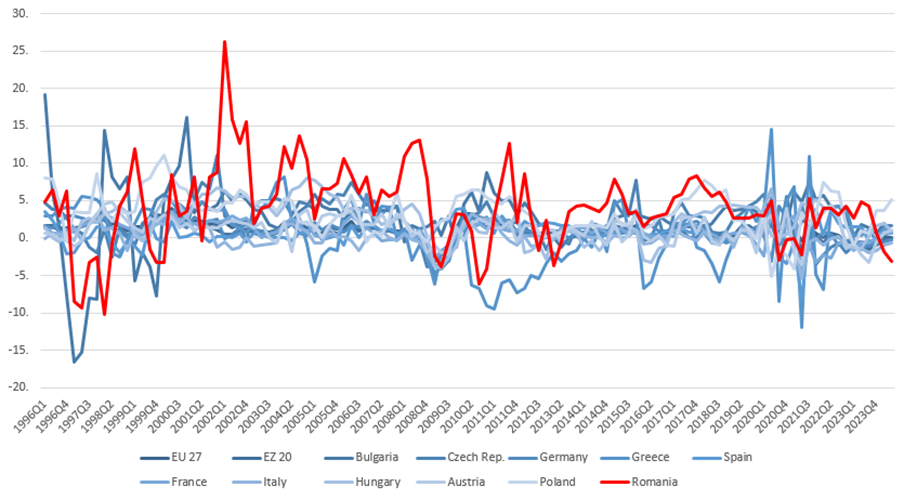

One of the important factors influencing competitiveness is labour productivity. From this perspective, Romania’s situation is mixed. Based on data provided by Eurostat and Bloomberg, figure 1 below shows that in Romania, for the period 2010-2023, the advance of labour productivity per hour worked in real terms was one of the most significant in the EU.

Figure 1: Annual variation of the real labour productivity per hour worked (percentage change compared to same period in previous year)

However, there are two elements that nuance the favourable evolution observed above. First, throughout the mentioned period of about 13 years significant volatility of labour productivity was recorded, among the largest in the region, as can be seen from the graph below.

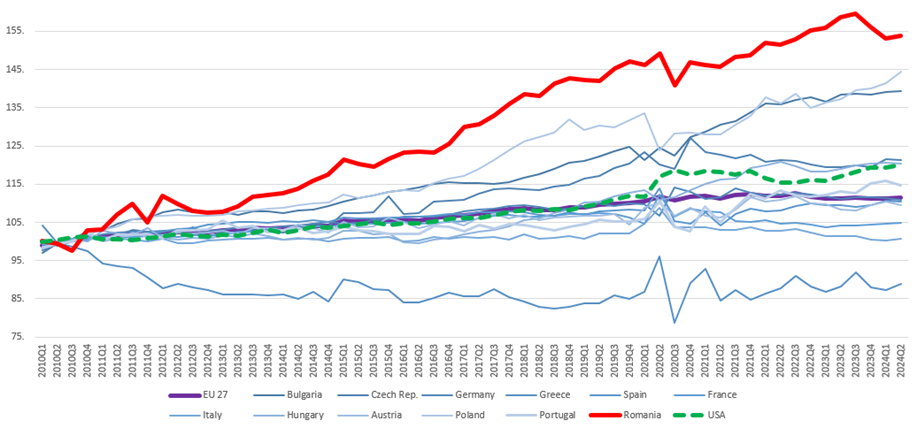

Figure 2: Trends in real labour productivity per hour worked (2010=100)

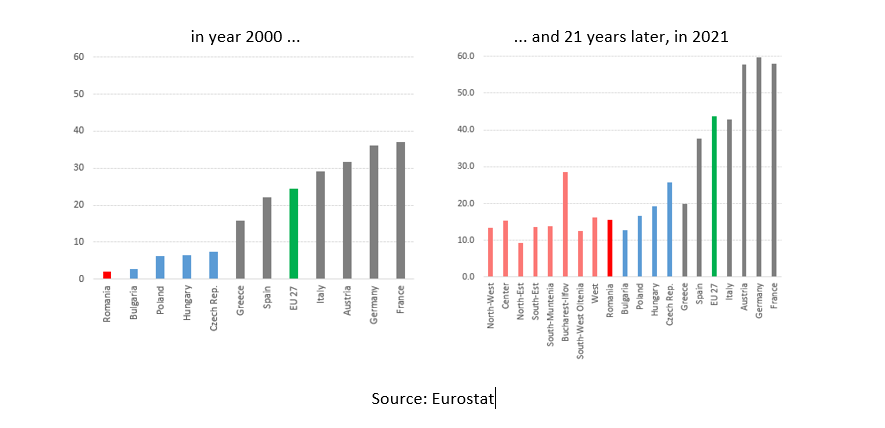

At the same time, the nominal level of productivity in Romania at the beginning of the analysed period was one of the lowest, below that recorded in Bulgaria and several times lower than in Poland, Hungary, or the Czech Republic (as can be observed in Figure 3).

Figure 3: Nominal labour productivity per hour worked (euro)

Consequently, while the dynamics of productivity in Romania have accelerated over the entire period, the nominal level recorded in 2021 remained lower in comparison to Poland, Hungary, and the Czech Republic. Nevertheless, it is important to note that this gap has significantly narrowed relative to its magnitude 20 years ago.

As in many other European countries, Romania also exhibits significant regional disparities in productivity levels, with the capital city area consistently concentrating higher added value and, consequently, a greater level of productivity (as illustrated in Figure 3 on the right). Notably, the north-eastern region ranks last among Romania’s regions according to this criterion. This is unsurprising given its lower levels of investment and less technologically advanced production capacities, with only a few exceptions in terms of successful attraction of investments over recent decades. On average, at the national level, we significantly lag behind many of our neighbouring countries, with whom we directly compete in the European single market, our primary export destination.

Therefore, there is still plenty of room for productivity growth, as evidenced by the current levels in neighbouring economies such as Hungary and the Czech Republic. Two of the solutions, in the medium and long term, are improving the skills of the workforce and increasing technological capabilities, respectively.

• For the first, the way to go is the continuous adaptation and improvement of workforce training, both at general and at professional level. It remains an ongoing objective; however, we have regrettably fallen significantly behind in recent years.

• For the second, the continuation of investments is of utmost importance; currently, we are taking important steps in attracting investments and the advance is significant, but we must address the increasingly visible risk of investment slowdown due to multiple causes.

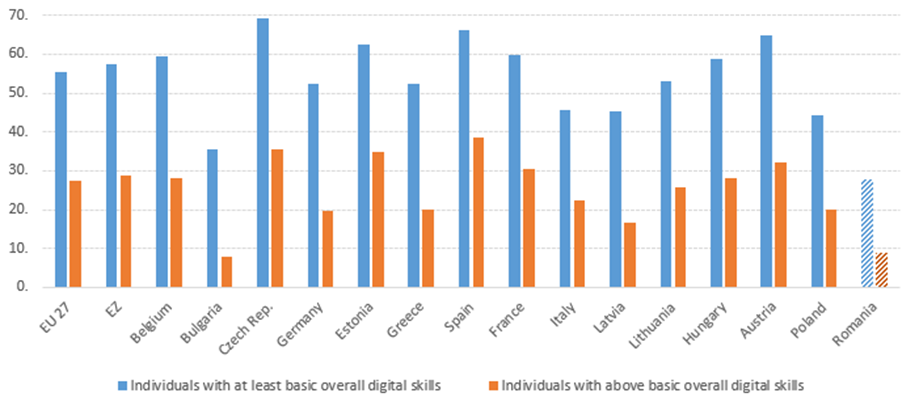

With reference to the workforce professional training, a relevant series of indicators that reflect the long-term outlook, especially in the context of the new economy, are those related to digital skills. In fact, digitalization is one of the areas covered extensively by the Draghi report, precisely because there are expectations that the advance of digital technologies will contribute to increase the productivity at the global level.

Romania continues to perform favourably on criteria related to the availability of high-speed Internet and the technologies employed for connectivity. However, other countries have also made significant strides in narrowing the gap that existed several years ago. For example, at the end of 2023, 95% of households had Internet connection with a speed of at least 1 Gbps in Romania, 82% in Hungary, and 75% in Poland (Eurostat data). Unfortunately, in Romania, the advantage of connectivity has so far been fully exploited only by companies in the IT services sector and by specialists in the field (IT engineers, programmers, etc.). Indeed, the added value created by these segments has undeniably contributed to GDP growth and the services trade surplus in recent years. Unfortunately, however, current trends indicate a slowdown in this sector, at international and European level. Conversely, a substantial increase in the significance of basic and mid-level digital skills is anticipated, since a higher proportion of the workforce equipped with such skills is likely to correlate with increased labour productivity, particularly in the context of the widespread adoption of new technologies across various economic sectors. Therefore, it is crucial to expand access to favourable Internet connectivity, leveraging this advantage to enhance the qualifications of both the current and future generations of employees.

Furthermore, in today’s world, it is difficult to envision education and training without the incorporation of digital skills, even at a basic level.

From this perspective, Romania unfortunately ranks last in the EU and at a considerably low level regarding the proportion of the population possessing at least basic digital skills, as illustrated in Figure 4 below.

Figure 4: Share of individuals with basic and above basic digital skills (2023)

The digitalization of public authorities can contribute to increase productivity in the private sector and improve the efficiency of public sector activities. Data published by Eurostat for the years 2022 and 2023 indicate that, for instance, the proportion of individuals in Romania who accessed websites or applications of public authorities at least once during the respective year is the lowest among EU member states, standing at approximately 23 percent. In comparison, this figure is 30 percent in Bulgaria, 71 percent in the Czech Republic, 76 percent in Poland and Hungary, and an average of 69 percent across the EU.

The data above highlight that Internet access is only a precondition, which does not lead to sustainable increases in skills and competences if not accompanied by an adequate education and training effort. This represents one of the key strategies to sustain an accelerated growth rate in labour productivity and to further bridge the gaps with neighbouring countries with which we compete for exports in the single European market.

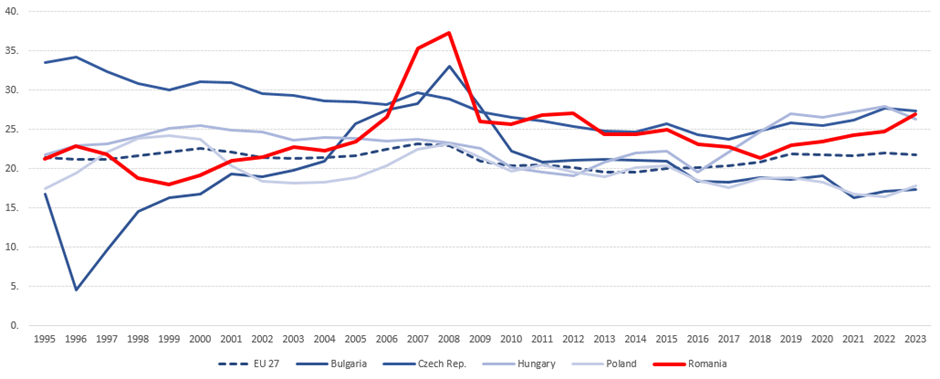

As previously mentioned, the second key strategy centres on investments. As illustrated in Figure 5, since the year prior to joining the EU, Romania has experienced a significant contribution of gross fixed capital formation to GDP, driven by investments from both the public and private sectors. The financing for these investments has been sourced from the national public budget, European funds, as well as domestic and foreign private investments.

Figure 5: Gross fixed capital formation as a percentage of GDP

The figure above indicates that, during the period from 2006 to 2015, Romania consistently ranked first in the region regarding the share of investments in GDP, alongside the Czech Republic, and significantly outpacing levels observed in Poland, Bulgaria, and Hungary, as well as the EU average. However, following the global financial crisis and particularly during the 2016-2018 period, there was a noticeable decline in this share, bringing it closer to the EU average. Beginning in 2019, however, the contribution of gross fixed capital formation to GDP began to rise again, reaching a peak of approximately 27 percent in 2023 – comparable to the figures recorded in the Czech Republic and Hungary, and surpassing the EU average of around 22 percent.

The data presented indicate that we are experiencing a favourable investment trend, which is crucial to sustain and direct as much as possible toward high-value-added sectors, which contribute to exports or to domestic supply of goods and services that can substitute imports.

To achieve this objective, securing financing is of paramount importance. In addition to public budget allocations and foreign direct investment, the role of domestic private capital is crucial. In this context, an approach from the Draghi Report that deserves attention in Romania is the emphasis on the necessity of encouraging and facilitating the mobilization of the population’s financial resources toward the capital market. Traditionally, a significant proportion of these resources in Europe is held in bank deposits. Sustaining a substantial investment effort to enhance competitiveness necessitates redirecting a larger share of these resources to capital markets—not only for equity participation in companies, but also for investments in bonds issued by them.

However, greater confidence is required, which can be achieved by enhancing the governance and investor protection framework. Consequently, at the European level, the consolidation and deepening of the Capital Markets Union project are becoming increasingly important. We can anticipate new updates to the regulatory framework concerning the capital market, focusing on the harmonization of supervision, as well as improvements in transparency and accessibility for both companies and investors.

In Romania, there has already been an increase in the participation of individuals in the capital market, evidenced by a rise in the number of active trading accounts and the amounts invested. This trend has occurred alongside substantial public participation in the issuance of state securities, many of which are listed on the Bucharest Stock Exchange.

The Draghi Report also highlights the increasing role that private pension funds can play, particularly in a sector that remains underdeveloped in Europe relative to the United States. Romania, in this context, possesses considerable potential for the development and consolidation of the progress made in recent years. It is noteworthy that private pension funds within Pillar II and Pillar III of Romania’s system, established in 2008, have accumulated over 8 million participants and hold assets amounting to approximately 8.6 percent of GDP (around 152 billion lei). These funds have acquired significant stakes in many major local companies listed on the Bucharest Stock Exchange and are also important investors in corporate bonds and Romanian government securities. The important role they have assumed in the economy over just 16 years has the potential for further growth, especially since the level of assets remains relatively low compared to the European average, which stood at 32 percent of GDP in 2022, according to the Draghi Report.

A third key element for enhancing competitiveness is the cost of raw materials and components. In this regard, recent years have witnessed significant changes for the European industry, impacting both the accessibility and pricing of raw materials and imported components. We are currently engaged in renewed discussions about the effectiveness and feasibility of rethinking supply chains, for both economic and strategic reasons.

Regardless of the short- and medium-term conclusions drawn from the debates among different schools of economic thought on this matter, there are specific markets and types of commodities where improvements can be made to enhance access and optimize the current design of market mechanisms, particularly concerning regulated components. A pertinent example is the electricity market, which is characterized by high price dispersion and a pressing need for substantial investment in generation, storage, transmission networks, and interconnection facilities.

In the electricity sector, Romania enjoys one of the most favourable positions in the region regarding the mix of primary resources utilized for production (depending on the period and conditions, approximately 60% of the total electricity generation comes from hydropower plants, the Cernavodă nuclear power plant, and renewable sources, such as wind turbines, solar panels, and biomass, in roughly equal proportions). However, the country experiences high price volatility, particularly when reliant on imports. This situation requires specific investment-driven solutions, as it leads to significant disruptions in economic activity that cannot be overlooked in the long term, especially given their impact on the competitiveness of crucial industrial sectors essential for external equilibrium.

The topics of interest highlighted in the Draghi Report can be further explored, and their analysis in relation to the current state of the Romanian economy, its potential, and the actions required for continued development is always beneficial. While some aspects may not receive sufficient emphasis from Romania’s perspective, I believe the report should primarily be viewed as an impetus to maintain focus on the necessity for adaptation and reform, fostering deeper discussions about the transformations facing all member states. Areas for action can be expanded and developed; for instance, future European policies may need to place greater emphasis on efforts to reduce economic disparities between regions and to reassess how the criteria for economic convergence and stability are defined.

In 1950, Robert Schuman articulated the vision that ”Europe will not be made all at once, or according to a single plan. It will be built through concrete achievements which first create a de facto solidarity” (https://european-union.europa.eu/principles-countries-history/history-eu/1945-59/schuman-declaration-may-1950_en).

I believe that the spirit of gradual yet ambitious integration, which fosters cohesion through clear objectives and solutions while garnering the support of all member nations, is essential to remember and uphold. Mario Draghi’s call for investment and reforms aimed at enhancing competitiveness merits further discussion, adaptation, and incorporation into future strategies at both the European and national levels.